This is an interesting post, written by doctor, author Alex Lickerman about reincarnation. Dr. Licker contradictorily practices Buddhism, and yet does not believe in re-incarnation.

———————-//—————————–

In this post, I’d like to consider seriously the issue of reincarnation. Or perhaps I should say, the problem with reincarnation. Though I practice Buddhism, I don’t actually believe in reincarnation. I suspect that my saying this will irk many of my Buddhist friends, who rightly consider the tenet of reincarnation central to Buddhism, as well as the indifference of anyone who doesn’t believe in reincarnation and therefore has little interest in an essay that points out the problems with a theory they already discount. Though I therefore risk having an audience of no one, I think the discussion will be an interesting one, because the real question at the heart of reincarnation is one of identity.

According to Wikipedia, the percentage of people who believe in reincarnation ranges from 12% to 44% depending on the country being surveyed (in the U.S., it’s 20%). And, I freely admit, such a belief may not be wrong: psychiatrist Ian Stevenson has conducted more than 2,500 case studies over a period of 40 years of children who supposedly remembered past lives. He methodically documented each child’s statements and then identified the deceased person the child identified with, and verified the facts of the deceased person’s life that matched the child’s memory. He also matched birthmarks and birth defects to wounds and scars on the deceased, verified by medical records such as autopsy photographs. While skeptics have argued his reports provide only anecdotal evidence, his data does seem to demand explanation.

The problem with reincarnation is that explanation, however, is twofold: 1) we have, as of yet, no way to verify it prospectively in an objective manner; and 2) we have no mechanism to explain how reincarnation might occur. Though reincarnation is indeed a central tenet of all sects of Buddhism, no sect of Buddhism posits the existence of a non-corporeal “soul”—an eternal, unchanging version of ourselves that’s capable of living independently of a brain and a body. Rather, in Buddhism, the self is viewed as something that has no “absolute” existence, as something that changes constantly from moment to moment, as well as something that’s capable of existing only within the confines of a physical brain.

Yet something of us, Buddhism argues, continues from life to life, something that makes us uniquely us. The sect of Buddhism I practice argues this “something” is our karma: the sum of all the effects we ourselves have created within our lives (like unexploded mousetraps that will be triggered at some point in the future) as a result of all the things we’ve ever thought, said, and done—not just in the past of our current life, but in all the pasts of all our previous lives.

And here is where I have a third problem with the Buddhist notion of reincarnation: how does the sum of all the effects I myself have created in the past add up to “me”? I can accept that all the things I’ve ever thought, said, and done (at least in this lifetime) have indeed, in some sense, created the person I am now. But do all my thoughts, words, and actions create my core essence—or arise from it?article continues after advertisement

Which leads me to ask what I think, in one sense, is a more interesting question than the question of reincarnation: namely, what is my core essence? The sense of self I feel and have always felt has seemed constant throughout my life, which is why I feel as if I even have a core essence. But a moment’s reflection reveals that what’s really remained constant is the feeling of the sense of self itself, not the content of that sense. Am I even remotely the same person I was at 5? At 15? Last week? A moment ago?

In one sense, obviously, yes. Something links the “me” that I am right now to the “me” that I was at 5 (and not, for example, to my wife as she was at 5). But what is that something? My memory? I’ve long ago forgotten most of what happened to me at 5. I remember being 5, but not the entirety of even one day from that year (in fact, I don’t remember the entirety of even one day from last week). If any content in my life remains constant, it’s not due to my remembering it, to my consciously holding it fast in my working memory so as not to forget it and thus myself. It’s because some things remain constant without my having to remember them or even think about them: essentially, my habits (which, are by definition, unconscious) and my beliefs (which, though they must be expressed in language, needn’t be consciously apprehended to influence behavior).

Given what we now know about the enormous size and power of the unconscious—about just how much of “us” lies beneath the surface of our conscious minds—we have to admit that the defining core of who we are may, in fact, be located mostly, if not entirely, beneath our awareness (our conscious minds being mostly spectators and interpreters of our unconscious selves).

But what does even this mean? That our unconscious beliefs and habits define who we are? Does our conscious awareness, the values we’re able to articulate to ourselves, have nothing to do with our identity? And what about our memories of who we’ve been? Without those, would not some essential part of the self be lost?article continues after advertisement

Many Buddhists would argue the sense that we even have a self is an illusion, that despite our feeling that a unique something lies at the core of what we are, such a something doesn’t, in fact, exist. And though I can’t answer any of the questions above, I find myself sympathetic to this point of view. I suspect the only thing constant about us is our sense that something about us remains constant, and that who we are is comprised both of stable parts (personality, beliefs, attitudes, and so on) and unstable parts (retrievable memories, moods, interests, and so on)—and that to change any one of them (whether in the realm of the conscious or unconscious) is to change who we are in proportion to their relative stability (changing a belief, for example—like a belief in God—would represent a major change; changing a mood, on the other hand, merely a minor one).

Certainly, those of us who’ve gone through major upheaval in our lives or experienced an abrupt and enormous leap in maturity at some point often pause to look back and imagine ourselves as a fundamentally different person from who we once were. But perhaps our inclination to label ourselves as “changed” only when we notice a large enough difference between who we are and who we used to be ignores the truth that we’re never not changing. Our lives are in constant motion, and to imagine that we could take a snapshot of them at any one point in time and somehow capture that which represents our essential selves strikes me as arguing that an actual snapshot of a flowing river represents its one true shape. So when people tell me they believe in reincarnation, the first question that comes to my mind isn’t about what evidence they think argues for the possibility. Rather, it’s this: just exactly what do they think gets reincarnated?

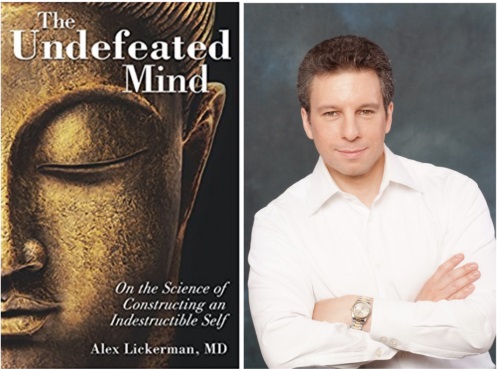

Dr. Lickerman’s new book The Undefeated Mind: On the Science of Constructing an Indestructible Self will be published on November 6. Read the sample chapter and visit Amazon or Barnes & Noble to order a copy.