In the autumn of 1956, Japan’s most renowned literary critic, the 54-year-old Hideo Kobayashi, engaged in taidan ( a “conversation” to be published in a magazine) with 31-year-old rising literary star Yukio Mishima.

Early that year Mishima’s novel, “The Temple of the Golden Pavilion,” had been published to widespread acclaim, following a series of best-selling novels such as “The Sound of Waves,” that had already been turned into films. In the course of their discussion Kobayashi exclaimed to Mishima, “You are exceedingly talented!” — and with that, the official seal was placed on Mishima’s meteoric rise to fame.

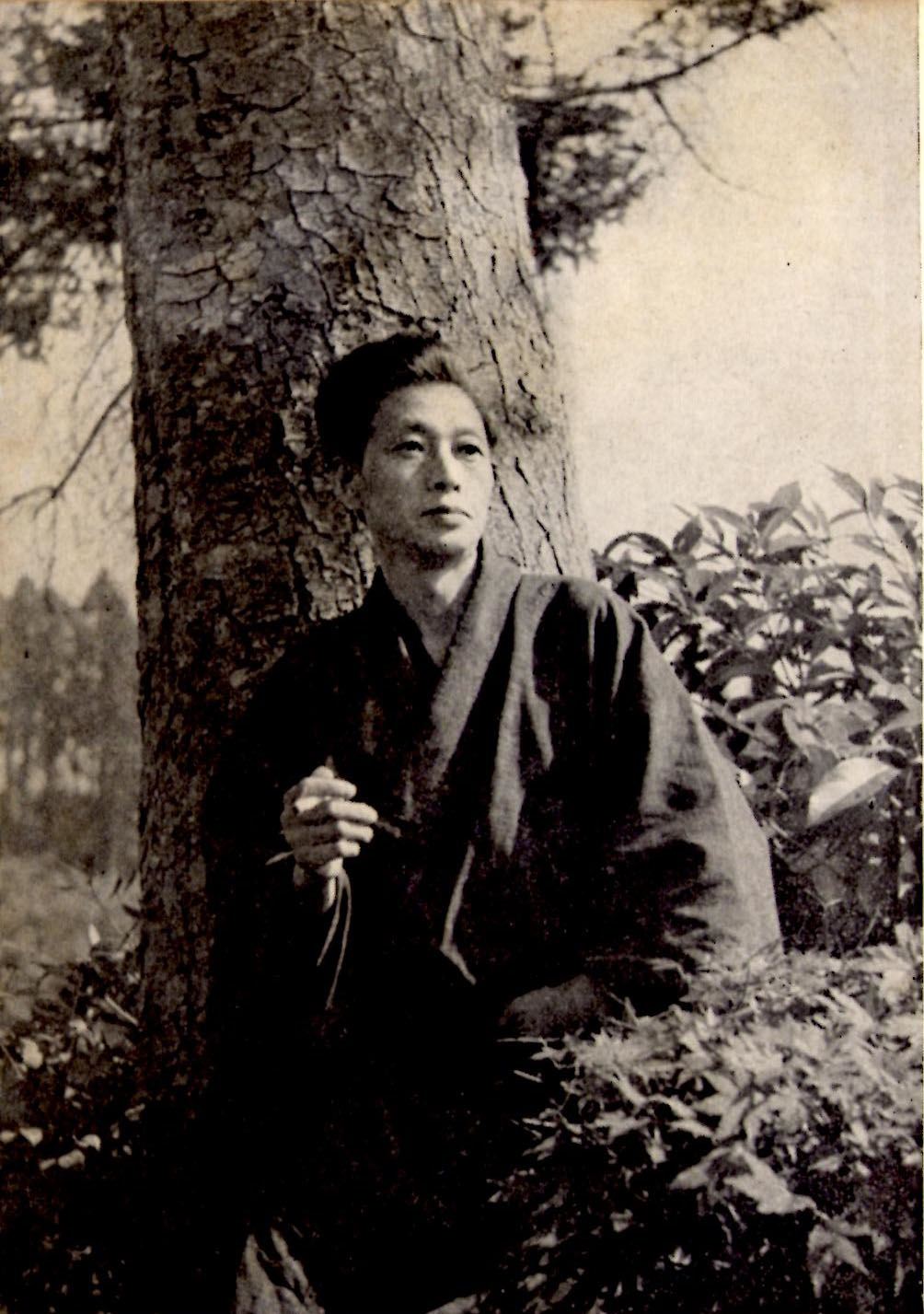

From the 1930s, Kobayashi (1902-83) had been the key figure in creating “literary criticism” as an independent art form. Before him, writing essays of criticism tended to be a sideline activity that prepared the ground for greater achievements, whether it was the Enlightenment critic Yukichi Fukuzawaputting his arguments for modernization into practice by setting up Keio University, or novelist Junichiro Tanizaki transmuting the pith of “In Praise of Shadows” into the prose of his monumental novel, “The Makioka Sisters.”

But it was Kobayashi who established “criticism” as an end in itself. In his youth in the early 1930s, he had been an associate of avant-garde writers Riichi Yokomitsu and Yasunari Kawabata, but whereas they concentrated on writing innovative fiction, Kobayashi devoted himself to prolific outpourings of literary criticism — stylish, opinionated and dismissive of ideology — in books on everyone from Russian maestro Fyodor Dostovesky to Japanese novelist Naoya Shiga.

As Japan became embroiled in war with China, Kobayashi assumed a stance sympathetic of the Japanese government, which would later invoke the ire of left-wing intellectuals, yet he managed to continue after the war as a best-selling and highly respected critic.

Others quickly followed in Kobayashi’s path, establishing professional critics as an important presence in the postwar literary scene. And no writer would feel their influence more keenly than Mishima. When “Confessions of a Mask” was published— his first novel as a professional author — it at first attracted little attention. Only after it was featured on a critics’ list of “notable books of 1949” did sales begin to skyrocket.

All of this stood in profound contrast to the literary milieu that had existed in Japan earlier in the century. When, for example, the novelist Natsume Soseki had published his novels between 1904 and 1916, there was hardly any “professional” critical scrutiny of his works at all.

Indeed, in his 1911 lecture “Hobby and Occupation,” Soseki advanced the idea that a writer was someone who wrote for himself, not for others, and it was purely by chance if this happened to meet with commercial success. In Soseki’s time, the professional critic simply did not exist.

Yet in the post-Kobayashi world of the 1950s, the critics stood as powerful arbiters of literary taste, writing influential reviews, forming the committees of sought-after literary prizes and conducting endless taidan in the magazines and newspapers of the day with notable authors and each other.

As the majority of literary works were serialized, critical scrutiny was applied in real time, potentially pressuring the author to conform to current vogues.

Although Mishima was feted by critics like Kobayashi during the 1950s, he was rankled by their power and by the end of the decade he was confident enough to pen a major novel, “Kyoko’s House,” which he decided to publish only as a complete book (a style known as kakioroshi). The book, Mishima believed, would “describe an age” and establish him as a “great author” capable of disregarding critics in the manner of Soseki or Mishima’s hero, Thomas Mann.

The result was a fiasco. “Kyoko’s House” sold well, but it was torn to shreds in a public discussion between five influential critics, putting Mishima into a funk from which he arguably never emerged.

The face-off between novelist and critics over “Kyoko’s House” can in many ways be seen as the moment when the decline in modern Japanese literature began. Early in the century, the finest minds in the country — the elite in the literary departments at top universities — had gone on to become the new generation of creative authors.

But now the country’s finest young minds increasingly aspired to be critics. By the 1980s and ’90s, if you wanted to read some of the smartest thinkers in Japan — hip writers such as Takaaki Yoshimoto, Takehiko Noguchi, Kojin Karatani and Yoichi Komori — you would be reading criticism, not novels. The golden age of Japanese literature may have been winding down, but the golden age of criticism was just beginning, applying an unprecedented degree of analytical flair to the social and literary revolutions that had buffeted Japan since the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

The literary figure who, above all others, was subjected to seemingly inexhaustible critical scrutiny was the man who in his own lifetime had been entirely untroubled by critics: Soseki. The conservative-leaning critic Jun Eto (one of the five who had savaged “Kyoko’s House” in 1959) wrote an incredible eight volumes of criticism and biography about Soseki. By the end of the 20th century, hundreds of other books of critical thought about him were in print.

There are many reasons for the decline of modern Japanese literature — the rise of television and internet media, the general stasis of Japanese society since the war and the dissipation of the intense stimuli of ideas from abroad — but the disconnect between criticism and literature must absolutely be counted among them.

It is ironic that Japanese criticism, which began in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) with Yukichi Fukuzawa as a forward-looking and inspirational force to a new wave of literature, is these days not directed to contemporary fiction, but to making sense of the explosion of unmediated literary talent that bloomed before the advent of professional critics led by Hideo Kobayashi.

Damian Flanagan

Source: www.japantimes.co.jp