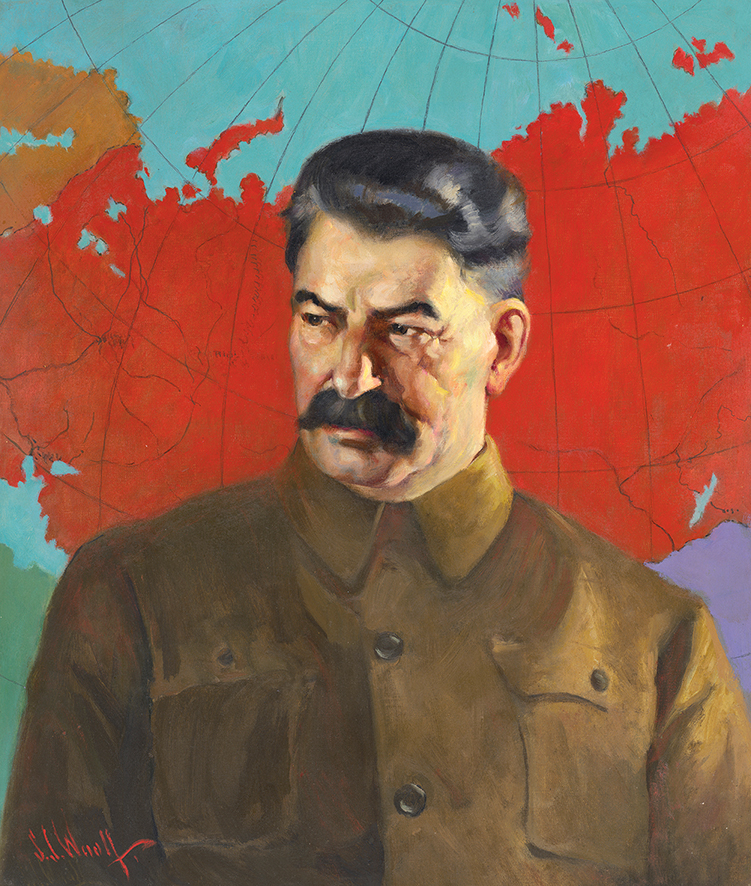

here is a sense in which the former Soviet Union was ruled by books. Stalin read avidly to learn how to apply the ideas that underpinned the new state, and protect it from danger. Here he followed the lead of the founder. Like Lenin, Stalin was an intellectual in power.

When some are comparing him with Vladimir Putin, Geoffrey Roberts’ summary view may be apposite:

“Stalin was no psychopath but an emotionally intelligent and feeling intellectual. Indeed, it was the power of his emotional attachment to deeply held beliefs that enabled him to sustain decades of brutal rule… Stalin’s unremitting pursuit of socialism and communism enabled his greatest achievements but at the cost of equally great misdeeds. Had he been more intellectual and less Bolshevik, he might have moderated his actions and achieved more at less cost to humanity.”

This distinction between Bolsheviks and intellectuals is interesting, and questionable. Lenin and Stalin were both of them prototypical intellectuals – ardent readers who looked to books to show how society can be transformed. Stalin was “a Marxist fundamentalist”, Roberts writes, for whom Marxism-Leninism was “rational and empirically verifiable but its ontological foundations were beyond questioning”. He never deviated from the Marxist world-view he adopted in his youth. Like Lenin, he regarded Marxism as a science that rested on unshakable truths. Both were ready to modify aspects of their ideology according to circumstances, but without ever questioning its most basic premises. In this respect Lenin and Stalin were like other intellectuals – liberal as well as Marxist.

Born in 1878, Stalin was educated in an Orthodox seminary in Tbilisi. It has been suggested that he retained elements of his training for the priesthood in his attitudes to politics, but there is little evidence of this. He never showed any sympathy for the heterodox Bolshevik movement of “god-builders”, led by the Soviet Commissar of Enlightenment Anatoly Lunacharsky (1875-1933), which aimed to turn revolutionary socialism into a religion. For Stalin as for Lenin, Bolshevism was the practical application of science – the opposite of religion, in their view.

Since Marxism-Leninism was a pseudo-science whose basic tenets Stalin treated as articles of faith, this was a misleading dichotomy. But it is true that he rejected any link between religion and the Bolshevik cause. It is inconceivable that he could have approved Alexander Blok’s celebrated verse drama The Twelve, composed in January 1918, in which the symbolist poet pictured Jesus leading 12 Bolshevik apostles through revolutionary Petrograd. The absence in Stalin of an apocalyptic Russian sensibility may be important, for it suggests a possible contrast with Putin.

Stalin’s Library is an account of the dictator’s intellectual and political development, but the core of the book is a long chapter detailing his pometki – the markings he made in the volumes he read. Quite often these were expletives. “Piss off”, “scumbag” and “ha ha” were some of his favourites. The significance of these markings – and the chief value of Roberts’ book – is in what they tell us of the workings of Stalin’s mind.

Stalin borrowed from the Lenin Library, and failed to return, a Russian edition of the memoirs of the “Iron Chancellor”, Otto von Bismarck. In the introduction, written by a historian, Stalin underlined the observation that Bismarck always warned against Germany becoming involved in a two-front war against Russia and Western powers. In the margin he wrote, “Don’t frighten Hitler.” In a translation of the memoirs of a British diplomat, he highlighted Edward Gibbon’s statement that the Romans believed troops should fear their own officers more than the enemy. Editing a short history of the Soviet Union, the most important changes he demanded related to its treatment of the emperor Ivan the Terrible (1530-84). He left intact the sentence, “Kazan was plundered and burnt.” Also left unchanged was the statement that under Ivan’s rule Russia “became one of the strongest states in the world”.

When not reading history and memoirs Stalin read much about science, including biology and linguistics. As is well known, he promoted the work of Trofim Lysenko, sharing the Soviet agronomist’s belief that the natural world must be remodelled by conscious human intervention. Less well known is the fact that he ridiculed the agronomist’s view that biology and other sciences had a “class character”, marking a report by Lysenko with the words: “Ha-ha-ha… and mathematics? And Darwinism?”

In linguistics, Stalin argued that languages were not class-based but ethnic and national in their origins. In time they would meld into a universal language, but that would happen only in a distant future when socialism had triumphed everywhere. In his role as what Roberts calls “editor-in-chief of the USSR”, Stalin edited articles on linguistics for publication in Pravda, as well as contributing to the paper himself. He criticised sharply the work of the Anglo-Georgian theorist Nikolai Marr (1865-1934) on the grounds that he adopted a “cosmopolitan” viewpoint that failed to respect national languages. Marr was not executed, imprisoned or exiled as were others Stalin criticised, but only because the linguist died, after a stroke had left him partially paralysed, before the Great Terror was fully under way.

Roberts praises Stalin’s “interpolations” in the linguistics debate as “a masterclass in clear thinking and common sense”. Maybe so, but Roberts tells us nothing of Stalin’s persecution of the clearest expression of cosmopolitanism in linguistics, the Esperanto movement. In 1925, one of the leading Esperantists, Alexander Postnikov, was executed after having been accused of spying. In 1936 there were mass arrests, with hundreds of members of Esperanto associations sentenced to long periods of exile. Leaders of the movement were shot, and it ceased to exist in the Soviet Union.

It might be argued that this was not an episode of much consequence in the grand scheme of Stalin’s life and work. It is not Roberts’ only omission, however. A close reader of Stalin’s Library could finish the book without knowing anything of the human costs of Stalin’s anti-Semitic campaigns. Roberts assures the reader that “the extent to which Stalin was anti-Semitic remains contentious”, while admitting he may have “used or acquiesced in” anti-Semitic prejudice in his assault on “cosmopolitanism”. He omits to mention that at least six of the nine physicians accused in the so-called “doctors’ plot” of 1951-53 were Jewish, while on the Night of the Murdered Poets on 12 August 1952, all 13 of the anti-fascist writers, actors and doctors executed by firing squad in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison were Jews. If Stalin was exploiting anti-Semitic prejudice, he did so convincingly.

Roberts says nothing regarding the scale of Stalin’s terror. He mentions the so-called Kremlin affair in 1935, in which 110 Kremlin staff, including cleaners, tea ladies and librarians were arrested, two of them shot and 108 imprisoned or exiled for “spreading slander about the state”. He passes over the hundreds of thousands who perished in the Great Terror. There is nothing in the book regarding the scale of the Soviet camp system and the huge numbers who spent time or died in it. Nor is there any mention in his discussion of Lysenko of the catastrophic Soviet famine of 1932-33. One might think millions of deaths merited a line or two, if only because they were partly the result of Stalin promoting a charlatan whose theories he privately derided.

In its examination of Stalin’s debts to the books he read, this is a pioneering work of scholarship. As an assessment of the dictator, it is tendentiously and at times absurdly revisionist. Stalin’s Library is a sequel to Roberts’ Stalin’s Wars: From World War to Cold War (2006), where he described the dictator – “a quietly charismatic figure”– as one of the 20th century’s greatest war leaders, who later tried to avoid the Cold War and hoped for peaceful coexistence with the West. Roberts denies wanting to rehabilitate Stalin, but that is, in effect, what he is trying to do.

Aspects of Stalin’s personality that were observed by his contemporaries are edited out from the self-effacing, book-loving figure Roberts presents. Stalin’s contemporaries were familiar with his taste for cruelty. His taunting of guests at late-night drinking sessions is well attested, as is his prolonging standing ovations to the point where his terrified audiences were sore-handed, exhausted and fainting. The manner in which he orchestrated the execution of Nikolai Bukharin is revealing. Before his show trial, in which he was accused of plotting to assassinate Lenin and Stalin, Bukharin wrote to Stalin begging to be executed by poison rather than by a bullet in the back of the head. In response, according to a report by a former secret service officer cited by one of Bukharin’s biographers, he was given a chair so he could sit and watch as 17 of his co-defendants were shot, one by one, until his time came. Bukharin’s fear and horror were multiplied many times over. There can be no doubt that the proceedings were scripted by Stalin. This was not the instrumental savagery of a Machiavellian despot aiming to terrify the population into obedience. A gruesome performance enacted in secret, it was calculated cruelty for its own sake.

Roberts is not alone in passing over blemishes in Stalin’s character, or in implying that what he sees as his great achievements somehow compensate for his great crimes. Like many others he gives Stalin the credit for helping defeat Nazism, though that belonged to more than 25 million Soviet citizens who died fighting it, the Russian winter and Hitler in launching the two-front war against which Bismarck had warned.

Why so many intellectuals glorified Stalin is a nice question. Part of the reason must be that Stalin was himself an intellectual. During the Second World War he enjoyed mass popularity in Britain, where he was feted as “good old Joe”. But the cult of Stalin in the West was the work of intellectuals who saw in him what they would like to be themselves: leaders with the power to reconstruct society on the basis of their ideas. HG Wells, Bernard Shaw, Sidney and Beatrice Webb and others revered Stalin for this reason. Writing in the Thirties, the French poet and essayist Paul Valéry observed that “the mere notion that the life of men could be organised on a collective plan is enough to give birth to the idea of dictatorship”. More than communism, it was the dream of overseeing a social order they had constructed that attracted intellectuals to Stalin.

Among Stalin’s admirers is Vladimir Putin. As Simon Sebag Montefiore recently noted in this magazine, guests visiting Putin’s office used to be asked to pick a book from Stalin’s library from those that graced Putin’s bookshelves. It is unlikely that the Russian president has read any of them. Books seem to play a small part in his life, and the writers he has cited are of another stamp from those studied by Stalin. Both the émigré White author Ivan Ilyin, one of whose works Putin claims to keep by his side, and the Orthodox theologian Nikolai Berdyaev (1874-1948), whom he has quoted in more than one of his speeches, were steeped in Russian spirituality. (Despite his Orthodoxy, Berdyaev was an intransigent opponent of Russian autocracy who would not have reciprocated Putin’s admiration.) As he has grown old in the Kremlin, Putin seems to have become possessed by the idea that Holy Russia must reassert itself against the decadent West.

At times Stalin may have been Russo-centric in some of his attitudes and policies, but there was nothing in him of this mystical Russian messianism. He was a lifelong rationalist, who did not condemn the modern West but aimed to surpass it. His Marxism-Leninism was ultimately based on an act of will, but his way of thinking was strategic, not apocalyptic. Here he was at an opposite pole from Hitler, with whom he is so often twinned. In his brilliantly illuminating Hitler’s Private Library: The Books that Shaped His Life (2008), Timothy Ryback comments that there were far more volumes on religion in the collection than he expected. Hitler’s interest in religion, Ryback observes, did not come from any need to believe in it. Instead he imagined himself in terms derived from religion, as a godlike force that could unmake the world.

Most comparisons of Putin with Hitler are overdrawn. Though the atrocities that are being perpetrated on his orders are mounting, he has not launched a colossal campaign of genocide as the Nazis did. His strategy in Ukraine – which aims to subdue the country by laying waste to its cities – is the same as that employed by Russian forces in Syria. In their turn of mind, however, Hitler and Putin may have something in common. No longer only the kleptocrat he has been during much of his time in power, Putin seems ready to destroy his country in order to leave his mark on history.

As Roberts shows in this flawed but valuable book, Stalin demolished Russia in an attempt to rebuild it on rationalist foundations. That is why Western intellectuals celebrated him: under his gruff exterior, he was one of them. Putin is different, and even more dangerous.

John Gray