Piano Sonata in B Minor, S.178

The life and career of Franz Liszt provide one of the most colorful chapters in the history of piano music. He is now principally known as a composer, but as a concert pianist he achieved staggering success. As a young man, Liszt had been entranced by the stage manner of the violinist Paganini, who inspired him to try for similar fame as a pianist. He worked hard on his virtuoso technique. Piano virtuosi were popular, but Liszt created a personality cult and a bravura style of performance which eclipsed the others. He more or less invented the model of a concert played by a single performer (before him, mixed programs with several performers were the norm). He was handsome and charismatic, played magnificently, was an inspired improviser, made thrilling arrangements of other people’s music, and performed his own pieces so theatrically that some listeners used to faint with emotion. The German poet Heinrich Heine wrote, “How powerful, how shattering was his mere physical appearance.”

Before a concert Liszt mingled with the audience, charming them with his witty remarks. He had a semicircle of chairs placed around the piano on stage so that illustrious guests could sit near him and converse with him between pieces. He added extra bits of his own invention to the pieces he was playing, improvising cadenzas, tremolos, double octaves, and trills even to iconic pieces like Beethoven’s “Moonlight” Sonata. He brought his silk gloves on stage and threw them down to be fought over by audience members. Women were said to carry his discarded cigar butts in their cleavages. When he broke piano strings, as he often did in his performances, people collected the broken strings and had them made into bracelets. There was even a phase where Liszt invited listeners to write a question for him (on any topic) on a slip of paper and put it into a hat, from which questions would be drawn out for the great man to answer from the stage. Clearly he was regarded as having more than musical authority.

Liszt’s touring years as a showman were concentrated into a decade between 1839 and 1848, after which he decided to accept his partner Princess Caroline von Sayn-Wittgenstein’s advice to devote himself to the more serious task of composition. He moved to Weimar, took up a post as Kapellmeister, retreated from his career as a virtuoso to compose, and only played concerts when he felt like it. He became a piano teacher, attracting a circle of gifted students whom he earnestly discouraged from doing things for effect (cynics have suggested that he just didn’t like the idea of anyone else emulating his success). He purged his life of frivolous elements, eventually returning to his childhood dream of taking holy orders. He became a “minor canon” in 1865, after which he was known as the Abbé Liszt.

The Music Room, by Mihály Munkácsy, 1878. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Martha T. Fiske Collord, in memory of her first husband, Josiah M. Fiske, 1908.

Liszt’s music has always been controversial. For some, it is emptily virtuosic and annoyingly melodramatic. For others, it is imaginative and innovative, with a subtle use of harmony which probably influenced Wagner and that looks ahead to Debussy and Ravel. Some pianists love Liszt’s music so much that they devote a large part of their concert repertoire to it. Others—uncertain if the means justify the effect—can never work up the motivation to learn all those notes. Musicologists have always admired Liszt’s mastery of “thematic transformation,” the way he reuses one theme so that it finds new life in another character or tempo. There are many examples in the Piano Sonata in B Minor, none more striking than the way the menacing repeated-note figure in the bass near the beginning is later slowed down into the dreamily beautiful contrasting theme marked “cantando espressivo.” For me, this transformation is a stroke of genius and the best thing in the sonata.

In 1839 the German composer Robert Schumann dedicated his wonderful Fantasy in C Major, op. 17, to Liszt. Liszt wanted to return the favor but had nothing he felt was worthy. Eventually in 1853 he completed his one piano sonata, which he dedicated to Schumann. Sadly, in 1854 a copy arrived at the Schumann household shortly after Robert had been committed to the mental asylum in Endenich. The pianist and composer Clara Schumann—Robert’s wife—received the score and had her friend Johannes Brahms play it to her. She found “nothing but sheer racket—not a single healthy idea, everything confused…And now I’ve got to thank him for it!” Her opinion was shared by Brahms and by quite a few leading German musicians. Despite this rocky start, Liszt’s sonata soon began to gather admirers and has never been out of the limelight.

Liszt himself liked playing it to visitors in Weimar, but always made a point of putting the score on the piano so that everyone could see it had been properly written down and was not one of the stormy improvisations of his younger years. In fact, the appearance of the manuscript does suggest that Liszt improvised it for himself and hurriedly notated it before he forgot what he had played. The sonata lasts around half an hour and is played without a break, though it does subdivide into several “movements” like those of a conventional sonata, or perhaps like a gigantic first-movement structure (theme + elaboration, contrasting theme + elaboration, development of this material, reprise with augmentation of the original elements). Liszt never declared whether it was inspired by a specific narrative, but many people have tried to find one that fits—ranging from the story of Adam and Eve in the Bible to Goethe’s Faust and Milton’s Paradise Lost. It opens with sinister premonitions, moves on to heroic outbursts, grandiose declarations, and lyrical episodes of great beauty. Weaving these ingredients together, it moves through brilliant pyrotechnics and stormy fugato episodes to a reprise in which the main themes are ennobled and glorified. The manuscript seems to show that Liszt first planned a triumphant ending, but his second thought was inspired: he ends with three long quiet chords whose fragile and evocative harmonies do indeed seem to point toward the future.

Robert Schumann’s C Major Fantasy, the dedication of which moved Liszt to reciprocate with something good of his own, seems to have left its own subtle mark on Liszt’s piano sonata. For example, the marvelous opening gesture of Schumann’s Fantasy, a descending melodic line, may have found its demonic echo in the dark opening of Liszt’s sonata, a descending melodic line in the bass. And the passionate way in which Schumann springs up the octave to restate his opening theme with more energetic dotted rhythms in a new key has a parallel in the way that Liszt begins the angry fast section that follows after the slow introduction. A little further on, Liszt’s “Grandioso” theme has something in common with a theme in the last movement of Schumann’s Fantasy (“Etwas bewegter”). It is pleasing to think that, even if poor Schumann never saw the sonata which Liszt had dedicated to him, he influenced Liszt’s imaginative world.

Nuages Gris, S.199

In his last years, Liszt suffered from episodes of depression. During this time, he wrote a number of piano pieces radically different in style from those of his earlier, flamboyant performing period. Gone are the torrents of notes which have inspired and terrified so many generations of pianists. The pages of his late piano pieces look almost minimalist, with few notes and simple lines. Liszt was always adventurous harmonically, but in these late pieces he goes much further, exploring the possibilities of unusual chords which are there not to indicate the direction of the phrase so much as to express a color or atmosphere in the present moment, an experimental style which makes his music sound as if it came from the era of Debussy and Ravel. The change of style is so marked that it feels almost as if he is trying to make amends for the excesses of his virtuoso pieces, or at least to make it perfectly clear that he no longer felt that way. Some of his circle felt that he had lost the plot at this time, but it may also be that he was adopting that brevity and concentration of expression which seems to mark many artists’ late works.

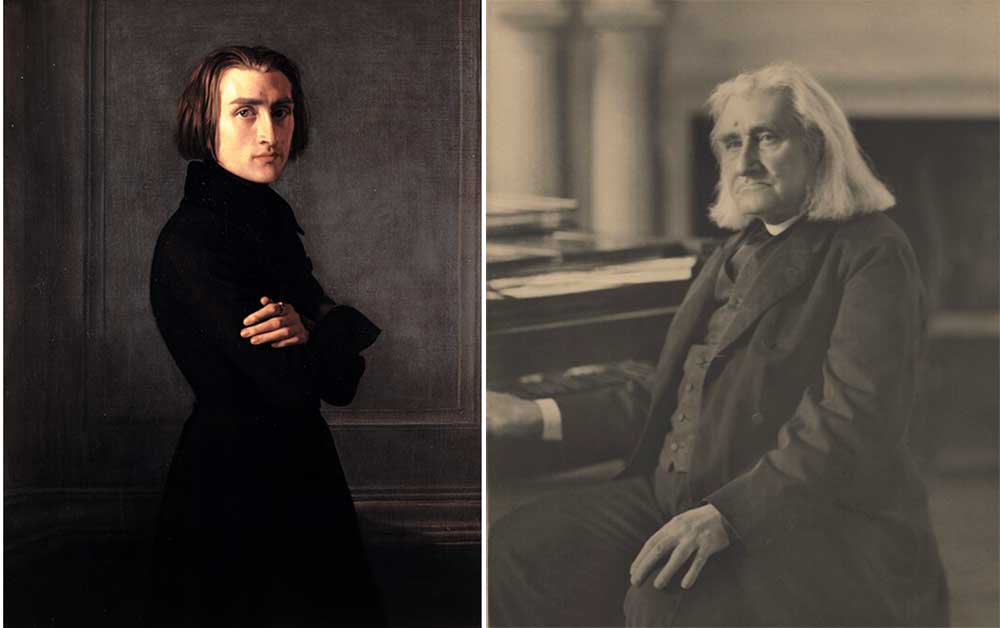

Left: Franz Liszt, by Henri Lehmann, 1839. Wikimedia Commons, Musée Carnavalet. Right: Franz Liszt, by Elliott & Fry, 1880. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Liszt was a close friend and supporter of the composer Richard Wagner. Their friendship was cemented when Wagner married Liszt’s daughter Cosima. Liszt often helped Wagner financially, attempted to give him good advice about how to run his life, and went to considerable lengths to promote Wagner’s operas when they were as yet unknown. As Wagner’s operas came out, Liszt often made piano transcriptions of parts of them. Like everyone else at the time he must have been struck by the harmonically daring Prelude to Act 1 of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, perhaps for more than one reason; some years before Tristan, Liszt himself had written a song, “Die Lorelei,” which has a harmonic gesture very similar to the opening of Wagner’s Tristan prelude. One might take the view that such harmonic language was simply “in the air” at the time, or one might suspect Wagner of borrowing an idea or two from his father-in-law.

One of Liszt’s best-known late piano pieces is Nuages Gris (Gray Clouds), written during a period of ill health and low spirits in 1881, after he had fallen down the stairs in Weimar and was confined to his bed. It is only forty-eight bars long, very quiet and sparing in texture. It seems to wander sadly here and there but is highly organized in a symmetrical structure. Nominally in the key of G minor, it seems to want to push delicately at the edges of this key with constant use of unexpected melody notes and intervals such as the G to C sharp we hear repeated over and over in the right hand. Liszt keeps gravitating to the “augmented triad,” a chord formed of two major thirds piled on top of one another, for example the F sharp–B flat–D chord we hear in the right hand in bar 11 and its three sibling chords which follow at two-bar intervals. As the piece goes on, the left hand rocks sadly back and forth between bass notes of B flat and A. In the final section of the piece, three ascending phrases in the right hand slowly cover the space of an octave.

These three phrases strongly evoke the opening of Wagner’s Tristan prelude with its sequentially rising phrases over similar harmonies. Having come to a half-close on F sharp in the treble, the note which we would expect to lead on to a close in G minor, Liszt then supplies the expected chord in the right hand but undermines it in the left with an ambiguous chord with A in the bass and another pile of thirds of various kinds on top of it. Throughout the piece, there is a sense of things not quite stated, of things hovering nearby in the dark (see the bass tremolos), of things trying to rise up and disappear. The refusal to end the piece with a gesture of closure makes it seem touchingly modern and reminds one of Liszt’s remark that his only remaining ambition was to “hurl my lance into the boundless realms of the future.”

Excerpted from The Piano: A History in 100 Pieces by Susan Tomes, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2021 Susan Tomes. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.

Source: https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/nothing-sheer-racket