László Földényi’s essays are a collection that will leave you feeling sharp and more cultured, says Tibor Fischer

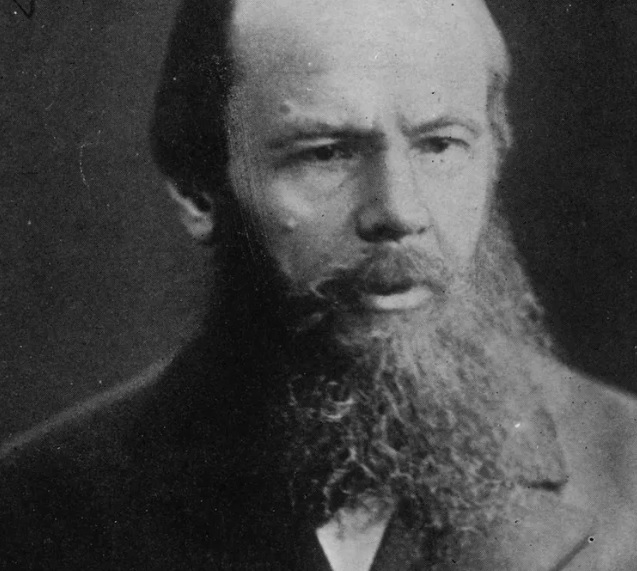

hat remains to fill the place of God, when God has been exiled and history and progress have also proved undeserving of trust?” asks László Földényi in the preface to his collection of essays, the wonderfully titled Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel In Siberia And Bursts Into Tears.

Földényi is a professor at the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Budapest and despite the elegant preface, the essays gathered here, written over a period of 15 years, clearly weren’t composed as part of any masterplan and have the feel of lectures given a turbo-charge. A lot of play with light and darkness is woven into these reflections as Földényi knows his art history, and he has a taste for the big questions: What is happiness? Has history ended?

For someone who has a post at the Film University, there’s surprisingly little about film here. Professor Földényi likes to read. A lot. One of the reasons I can rarely bring myself to read books by British academics is that, despite a sometimes esoteric vocabulary, they have a feeble command of language and a very limited cultural range (Barthes, Foucault, Zizek, climate change). I can’t think of anyone in this country (anyone alive, that is) who has the sweep Földényi demonstrates.

I worry when I see the name Hegel. Without indulging in the poetic excesses of Nietzsche, one of my main reservations about Hegel is that it’s often very hard to understand what he means. There’s plenty of room for interpretation, which partly explains his popularity in the arts faculties of the world.

The star turn in the collection is the eponymous piece about Dostoyevsky. Földényi speculates that Dostoyevsky, reprieved from death row, banished to the back of beyond, nevertheless might well have got hold of a copy of Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of World History and read the passage: “We must first of all eliminate Siberia … the whole character of Siberia rules it out as a setting for historical culture and prevents it from attaining a distinct form in the world-historical process.”

I doubt that Dostoyevsky needed Hegel to break the news that he had fallen off the edge of the world, as he was freezing his arse off in the absolute zero of culture, but, of course, ironically, his time in Siberia probably made him as a writer.

Hegel also dismisses Africa as not worthy of consideration, and here Földényi gets a bit “academic” and takes off into space. “Behind Hegel’s vehement repudiation of Africa and Siberia lies his secret wish to assassinate God,” he writes. Földényi then attempts to justify this statement but didn’t manage to convince me.

The first and final essays feature Elias Canetti. I’ve tried and I’ve tried over the years, but I can’t fathom why Canetti is considered a great writer (admittedly I’ve only read him in translation).

Similarly, Antoine Artaud has always struck me as a near-charlatan (you mean theatre doesn’t have to be actors in togas declaiming Racine under a floral proscenium arch? Why didn’t anyone think of that before?). However if you teach at the Theatre University, I suppose you can’t really ignore him.

There’s a good piece on Heinrich von Kleist and his famous suicide, although I reached the point decades ago when I decided I didn’t want to read about Kleist’s suicide ever again. If you write an essay, as the young von Kleist did, with the title “A Sure Way to Find Happiness And To Enjoy It Even in the Greatest Tribulations”, you’re just begging for the cosmos to give you a good kicking. However, suicide seems to be very beneficial for a writer’s career for some reason. I’d wager if Virginia Woolf had hung on through the war years and ended up tending roses in Cheltenham in her eighties, she’d be out of print.

Oddly, Hungarians hardly appear in these pages. The Nobel Laureate Imre Kertész gets a couple of walk-on parts to talk about Auschwitz and democracy, and there’s a mention of Béla Hamvas, an essayist Hungarians have, unsuccessfully, tried to persuade me is a genius.

Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel In Siberia And Bursts Into Tears, smoothly translated by Ottilie Mulzet, is a book that will leave you feeling sharp and more cultured, a sort of intellectual Red Bull. However, I’d argue the late Mihály Szegedy-Maszák was a more original cultural commentator and that if Yale is looking for another volume to translate from the Hungarian they should consider Szegedy-Maszák’s Word, Picture, Music: An examination of the similarity of the arts.