In “The Unwomanly Face of War,” an oral history of World War II, the Nobel Prize-winning writer Svetlana Alexievich recounts a strange little story. A woman leaps into dark water to rescue a drowning man. At the shore, however, she realizes it is not a man she has hauled from the water but a gigantic sturgeon. The sturgeon dies.

Censors initially cut the scene from Alexievich’s book. You’re not asking about the right things, they remonstrated. Focus on bravery, on patriotism. Let’s have less about fear, and less about hairstyles. There was no place in the canon for her sort of wartime stories, Alexievich recalled in an interview with The Paris Review. There was no place for reality, which comes stuffed with sturgeons and all manner of misapprehensions and muddle; reality, which shows notable indifference, if not outright hostility, to plot.

Perhaps an alternative canon exists, in the work of oral historians like Alexievich, and in the deeply reported narratives of journalists like Barbara Demick. The method is programmatic openness, deep listening, a willingness to be waylaid; the effect, a prismatic picture of history as experienced and understood by individuals in their full amplitude and idiosyncrasy. Alexievich collects the daydreams of her subjects. In Demick’s impressive account of life in North Korea, “Nothing to Envy,” she described a society on the brink of starvation, cut off from the world, lacking even electricity. But she told love stories, too. Darkness proved to be a surprising boon; some North Koreans told her they grew to need it, as it conferred the only freedom they knew. Young people fell in love in the dark: “Wrapped in a magic cloak of invisibility, you can do what you like without worrying about the prying eyes of parents, neighbors or secret police.”

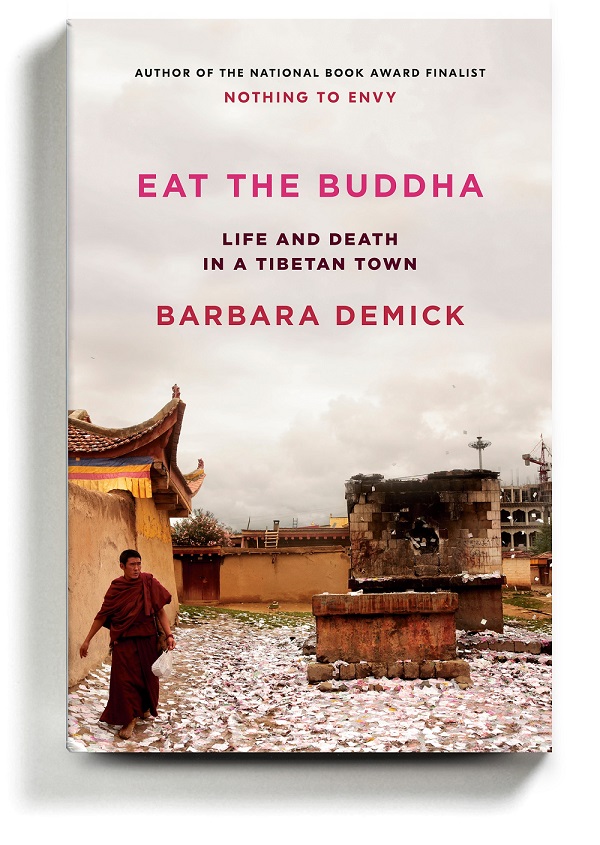

“Eat the Buddha” is Demick’s third book, all of them told in rotating perspectives — a model inspired by John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” and one she has made her own. In “Logavina Street,” she described daily life during the Bosnian War through the lens of one neighborhood in Sarajevo. “Nothing to Envy” followed six refugees from the port city of Chongjin. The close focus gives her work its granularity, but it also allows her to crosscheck the stories of her subjects. “Good reporting should have the same standard as in a courtroom — beyond a reasonable doubt,” she has said. In her latest, the masterly “Eat the Buddha,” she profiles a group of Tibetans with roots in Ngaba County, in the Chinese province of Sichuan, which bears the gory distinction of being the “undisputed world capital of self-immolations.”

Despite the Buddhist taboo against suicide, some 156 Tibetans — at the time of Demick’s writing — have set themselves on fire in recent years, protesting China’s rule. They have perfected their technique, wrapping themselves in quilts and wire to prevent rescue, dousing themselves in gasoline and swallowing it, too, to ensure they will burn from the inside. Almost a third of these people — monks, mothers, ordinary citizens — have come from Ngaba and the surrounding region.

Why Ngaba? “Why were so many of its residents willing to destroy their bodies by one of the most horrific methods imaginable?” This mystery hooked Demick, who arrived in China in 2007 as the Beijing bureau chief of The Los Angeles Times. On the face of it, Ngaba is better off than many of its counterparts, she observes. The residents are comfortable, the infrastructure comparatively decent. (The government invested in a “blitz” of modernization in the hopes of quelling the uprisings). Some attribute the protests to the harsh and oppressive police presence. But Demick argues that the roots run deeper. Ngaba was the site of Tibet’s first meeting with Chinese Communists, in the 1930s. “The people of this region have a particular wound causing excessive suffering that spans three generations,” the monk Kirti Rinpoche testified before a U.S. congressional commission in 2011. “This wound is very difficult to forget or heal.”

Fleeing Nationalist forces, the Red Army marauded through monasteries. They burned holy books and manuscripts, and survived by boiling and eating the skin of drums and the votive offerings to the Buddha (from which the book gets its title). Demick traces this first encounter, and the ensuing violent history, through the testimonies of her cast of characters: students and teachers, market sellers, the private secretary to the Dalai Lama, the former princess of the Mei kingdom.

These scenes are narrated as flashes of memory, anchored by the types of details children remember, giving them an unbearable vividness and horror. One man recalls hiding himself as a little boy when his house was invaded by Chinese soldiers. He emerged to find his grandfather gone and grandmother badly shaken, her scalp bleeding. He remembers wondering: Where are her pigtails? The former princess remembers being so curious about the Chinese at first, so delighted to meet them. Her mother joked that she offered grass to their trucks, the first vehicles she had ever seen. She thought they were horses.

Those who self-immolate today are the grandchildren of those who participated in the early uprisings, Demick writes. Having imbibed the Dalai Lama’s teachings of nonviolence, they can only bear to hurt themselves. They bear the scars of the “Democratic Reforms” in eastern Tibet that began in 1958. “Tibetans of this generation refer to this period simply as ngabgay — ’58. Like 9/11, it is shorthand for a catastrophe so overwhelming that words cannot express it, only the number,” Demick writes. “Some will call it dhulok, a word that roughly translates as the ‘collapse of time,’ or, hauntingly, ‘when the sky and earth changed places.’”

Tibetans were forced into cooperative living, stripped of their herds and land. Their yaks — sources of their food, clothing and light (candles were made from yak fat) — were seized and slaughtered, recalling the American government’s devastating policy of culling the Lakota’s bison. Daylong public “struggle sessions” were instituted — rituals of public humiliation in which those accused of perceived infractions were forced to admit to crimes and submit to verbal and physical abuse — with children forced to observe and cheer along. Some 20 percent of the population was arrested and held in prisons that were often only pits in the ground filled with hundreds of people. An estimated 300,000 Tibetans died.

Demick covers an awe-inspiring breadth of history — from the heyday of the Tibetan empire, which could compete with those of the Turks and Arabs, to the present day, as the movement for Tibetan independence has faltered and transformed into an effort at cultural and spiritual survival. She charts the creative rebellions of recent years, the efforts at revitalizing the language and traditions, Tibetans’ attachment to the Dalai Lama (and their criticisms). Above all, Demick wants to give room for contemporary Tibetans to testify to their desires. If the spectacular horror of the self-immolations first attracted her interest, she finds, at least among her sources, demands that sound surprisingly modest. They want only the rights enjoyed by the Han Chinese, she writes — to travel, hold a passport, to study their own language, to educate their children abroad if they wish.

Her forecast is pessimistic. Only in North Korea has she witnessed such smothering surveillance and high levels of fear, she writes, accelerated by technological developments like a social credit system in development that will prevent “untrustworthy” citizens from employment, buying plane tickets and using credit cards.

In Ngaba, the last Tibetan-language school — the last one in all of China — has switched to teaching primarily in Chinese. Meanwhile, across the country, Demick notices the same red billboards springing up, proclaiming the latest propaganda: “TOGETHER WE WILL BUILD A BEAUTIFUL HOME. BEND LOW. LISTEN TO WHAT PEOPLE SAY.”