Everyone’s favorite aristocratic dandy was also an outspoken socialist

In 1884, George Bernard Shaw joined the newly formed Fabian Society, which was dedicated to advancing democratic socialism in Great Britain, primarily through the gradual dissemination of socialist ideas. Some time later, Shaw spoke at a meeting of the Society in London, with an unexpected attendee: Oscar Wilde. Wilde was so taken by the subject that he produced his own views on it in an essay entitled, “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.” In Oscar Wilde: A Certain Genius, biographer Barbara Belford recounts how Shaw reacted to the essay, saying, “It was very witty and entertaining, but had nothing whatever to do with socialism.”

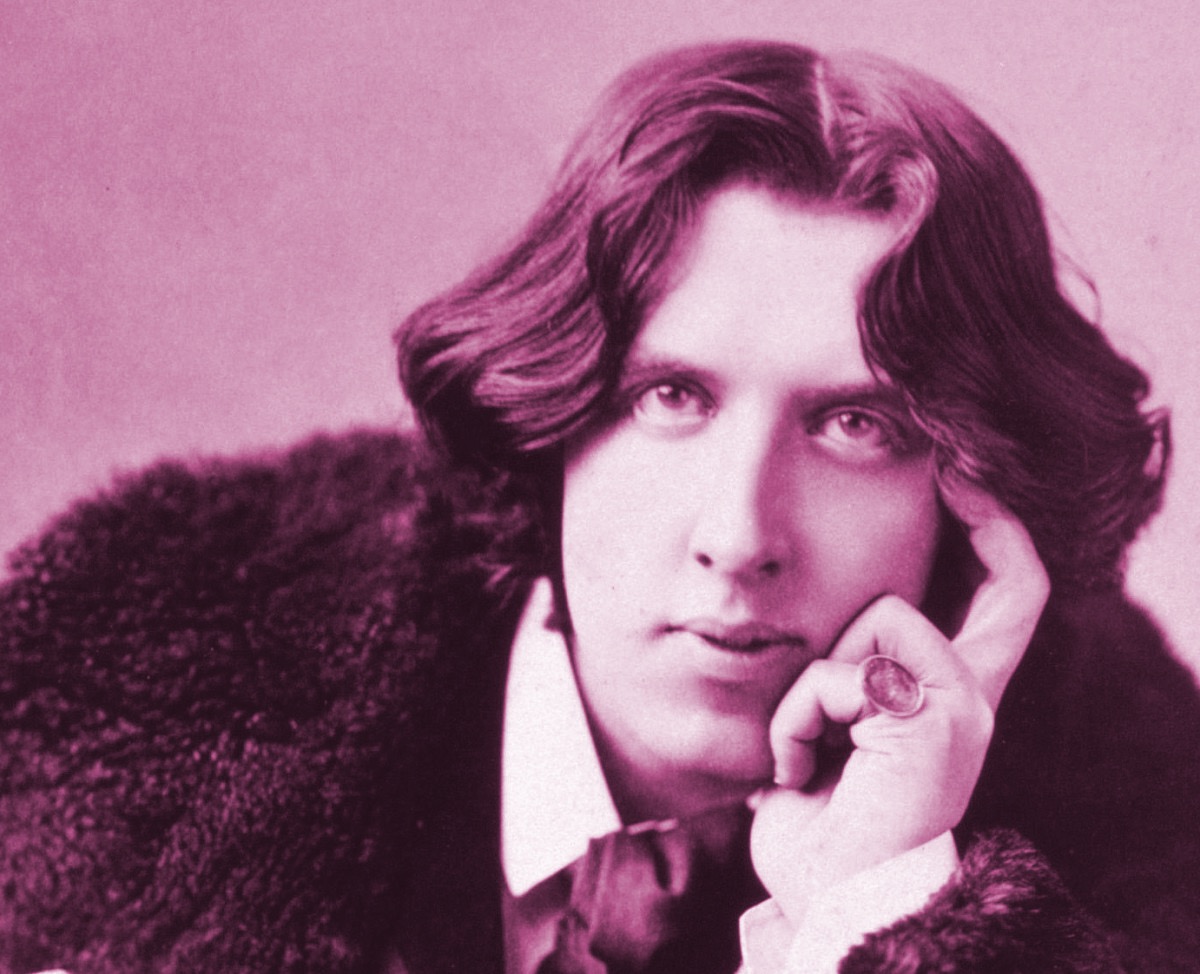

It’s true that Wilde’s views departed radically from Shaw’s and those of the Fabian Society. But although Wilde is most often remembered as an aristocratic dandy (a “snob to the marrow of his being,” according to Shaw), the politics that he espoused were indeed a form of socialism — namely, libertarian socialism.

Although Wilde is remembered as an aristocratic dandy, the politics that he espoused were indeed a form of socialism.

Considering his upbringing in mid-19th century Dublin, it’s not surprising that Wilde felt an affinity for socialism. His mother Jane was an outspoken supporter of Irish nationalism, which had a strong socialist current, in contrast with English imperial capitalism. (James Connolly, who would be one of the leaders of the Easter Rising, first founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party.) While less overtly political, Wilde’s father William also passed up the prosperous career of a private physician to found a charitable hospital. The couple raised Wilde — born October 16, 1854 — in middle-class comfort, but would not have been able to send him to Trinity College, and then to Oxford, had he not won successive scholarships. In fact, the family was nearly bankrupt upon William’s death, when Wilde was just 21 years old.

Wilde made a name for himself as a dandy in his early adult life, but that was deceptively a period of financial precarity and desperate work. Spending the last of his inheritance, he affected a decadent air, attending the opening nights of London theaters in a velvet coat, silk stockings, and flowing tie — while also doggedly, though unsuccessfully, attempting a career a playwright and poet. His first break came in 1882, when he undertook a tour of the United States, partly as a lecturer on aestheticism, partly as an aesthete attraction. Wilde loved to play the sloth (“Ambition is the last refuge of the failure,” he wrote in “Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young”), but as his grandson Merlin Holland describes in his introduction to Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, the tour was extremely demanding:

The programme, originally planned to last four months, stretched to nearly a year and it was far from being just a sedate lecture tour for the self-appointed ‘Professor of Aesthetics’ …. He faced a punishing schedule of 140 lectures in 260 days from the East to the West coast and up into Canada without the help of air travel and fast trains.

Without any other stable source of income, Wilde continued touring in England. Forced to spend months away from his wife Constance and young sons Cyril and Vyvyan, he was finally offered the opportunity to settle in London with the editorship of a women’s magazine from 1887 to 1889. During this period, he published The Happy Prince and Other Tales and worked on The Picture of Dorian Gray, which first appeared in magazine form in 1890. When “The Soul of Man Under Socialism” was published the following year, Wilde was finally beginning to see some success as an author, rather than a character.

While the Fabian Society represented the most mainstream current of socialism in Great Britain — it would help found the United Kingdom’s Labour Party in 1900 — Wilde’s essay presents an enticing alternative. Shaw and the Society promoted electoral means to political reform that would gradually improve the condition of the working class, such as the introduction of a minimum wage. (The Society takes its name from Fabius, the Roman general who fought Hannibal with attrition, rather than open conflict.) In contrast, Wilde argues that such “remedies do not cure the disease: they merely prolong it.” Rather than attempting to set the existing system of power toward incremental improvements, he advocates a much more revolutionary approach: abolition of both private property and government, which would simultaneously solve the problems of poverty and crime. Wilde illustrates his reasoning with an understanding of automation that should put many technologists to shame:

Up to the present, man has been, to a certain extent, the slave of machinery, and there is something tragic in the fact that as soon as man had invented a machine to do his work he began to starve. This, however, is, of course, the result of our property system and our system of competition. One man owns a machine which does the work of five hundred men. Five hundred men are, in consequence, thrown out of employment, and, having no work to do, become hungry and take to thieving.

Wilde not only argues that freeing wealth from the hoarding of private property would reduce poverty, but insists that, with the corresponding reduction in crime, the state would no longer need to govern — that is, to forcefully control individuals. Instead, the state could focus on developing automated systems to equitably provide the necessities of life, while individuals thus freed from want and work could dedicate themselves to producing the beauties of life through art or other forms of self-actualization. In this way, he reasons that “Socialism itself will be of value simply because it will lead to Individualism.” In the wake of the USSR, it’s understandable that Belford, writing in 2000, describes Wilde as “more an anarchist than a socialist,” especially as he had the foresight to condemn “Authoritarian Socialism.” But the two impulses — of common good and of individual freedom — could otherwise be reconciled as “libertarian socialism,” an anti-authoritarian, anti-capitalist political philosophy with roots that predate Marxism.

In libertarian socialism, Wilde not only saw the potential for his realization as an artist, but his liberation as a gay man.

Wilde had his reasons to rail against both the economic system and government that he was subjected to. As mentioned, capitalism was doing him no favors; it would continue plaguing him up to his death on November 30, 1900, in Paris, where he had been trying to eke out three years of exile in utter debt. And of course it was the British government which had exiled him, as well as precipitated his demise: Convicted of “gross indecency” for his homosexuality in 1895, Wilde served two years of hard labor and suffered an ear injury in prison, which eventually lead to a fatal case of cerebral meningitis, taking his life at just 46 years old.

In libertarian socialism, Wilde not only saw the potential for his realization as an artist, but his liberation as a gay man. Belford writes that Wilde had realized his homosexuality, with his literary-executor-to-be Robert Baldwin Ross, shortly before penning “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.” The law that Wilde would be prosecuted under had just been passed in 1885, so he was not at liberty to discuss the subject openly in his essay, but the suggestion is there in lines like, “[Socialism-cum-Individualism] converts the abolition of legal restraint into a form of freedom that will help the full development of personality, and make the love of man and woman more wonderful, more beautiful, and more ennobling.” Shaw and the Fabian Society could claim a shallow victory for their “prolonged remedies” (as Holland notes, homosexuality was decriminalized in the United Kingdom in 1967), but Wilde understood that, for some, there is no time to wait.

It is worth wondering, though, just how much more radical Wilde’s political vision would have been if he had lived longer — just long enough, perhaps, to seriously consider humanity’s ascent beyond the boundaries of this planet. After all, he was already so close to fully automated luxury gay space communism.

Arvind Dilawar is a writer and editor with work in Newsweek, Guardian, VICE, and elsewhere.