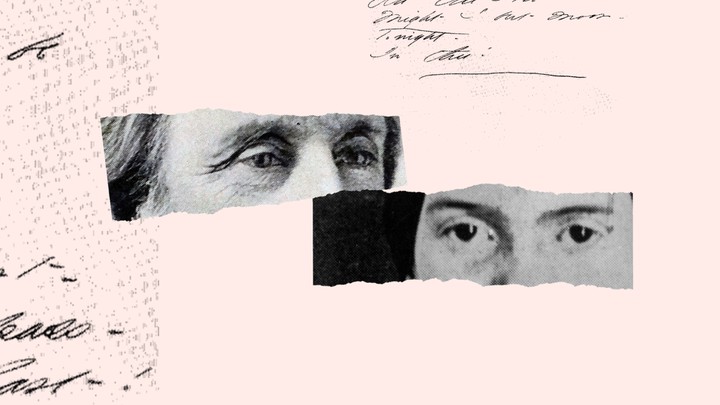

After eight years of letter writing, the author Thomas Wentworth Higginson finally met the reclusive poet face-to-face.

by Martha Ackmann

“My dear young gentleman or young lady,” the essay in the April 1862 issue of The Atlantic began. Thomas Wentworth Higginson went on in “Letter to a Young Contributor” to offer advice to would-be writers seeking to publish. Use black ink and quality paper, and avoid sloppy dashes. That beginning line, with its two-word invitation to ladies, may have caught the eye of a 31-year-old woman living in Amherst, Massachusetts—a woman who did not entirely agree about the dashes. Emily Dickinson read the essay and then took the most unprecedented step of her life. She wrote Higginson—a stranger to her—directly and sent four poems, along with a note. “Mr Higginson,” she wrote. “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?” Dickinson’s letter set into motion a correspondence with Higginson that lasted almost a quarter of a century. Eight years after writing her initial letter, on August 16, 1870, Dickinson and Higginson finally met face-to-face.

Higginson’s visit would be no ordinary call for Dickinson—not that she received many guests. Her great literary productivity of the Civil War years had tapered off. She had stopped collecting her poems in stitched booklets—fascicles—and new poems remained unbound on loose sheets. Nearly 40 years old, she was more patient, less insistent, and more forgiving of perceived slights from those close to her. Although others around her were busy with their own lives, she did not feel as forsaken as she once had. Dickinson’s sense of self made the difference. She knew who she was. She no longer was hoping to make her family proud. The hundreds of poems in fascicles and on sheets hidden away in her room bore witness to what she already had accomplished. In her letters, Higgison had noticed, she no longer signed her name on a card slipped inside the envelope—a game played as much for effect as reticence. Largely gone, too, were the callow signatures of “Your Gnome” and “Your Scholar.” Now she signed her name with a single word: “Dickinson.” That is who she had become.

Higginson was excited and nervous about paying calls. As a boy, he was shy around women outside his family. To mitigate awkwardness, he would write down conversation topics. If tongue-tied, he would pull the paper from his pocket and select a matter to discuss. But Higginson had plenty of questions for Dickinson, chief among them inquiries about her seclusion. At times, her talent made him reluctant to answer her letters, aware he never could match her artfulness. He was clumsy with words, he told her, and often missed the fine edge of her thought. But he forced himself to put aside timidity and continued to write, knowing what he could not offer in useful criticism he might be able to offer in dependability, friendship, and generosity. Higginson thought that she needed someone—a person who admired her, even if he did not always understand what she was saying. “Sometimes I take out your letters & verses, dear friend,” he wrote, “and when I feel their strange power, it is not strange that I find it hard to write & that long months pass. I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that perhaps if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkles of light.”

Higginson was exhausted as he prepared to meet Dickinson in her Amherst home. He had spent the past year writing two books. The Atlantic had serialized his first novel, Malbone: An Oldport Romance, and then there was an upcoming book based on his Civil War diary. Living in Newport, Rhode Island, had also lost its allure. He now found society life superficial and draining. Perhaps Dickinson knew better after all how to preserve the energy needed for creativity. The hotel she had suggested that he stay at was convenient: four stories tall, in the center of town, with a dining room, as well as a livery stable around the corner. It was not as hot as it had been that summer, but it was dry. Many town wells had dried up, and the Connecticut River was low, with brown banks stretching from shore. The town common looked terrible—scraggly and barren.

Calling card in hard, Higginson set out walking toward the Dickinson Homestead in long, loping strides. He followed the road down a gentle slope until it leveled off near a copse of trees and the start of a wooden fence. The fence marked the beginning of the Dickinson property. First the Evergreens, the stately home of the poet’s brother and sister-in-law, then the Homestead, the Dickinson-family manse. The walkway rose again as it approached the front steps—a not-so-inconsequential reminder of the family’s prominence. Higginson took in the sight so he could tell his wife everything. A large house. Like a country lawyer’s. Brick. Flower and vegetable gardens to the east and an apple orchard. Pears too. From where he stood, he could see the train depot and the distant line of the Pelham hills. He knocked, presented his card, and was ushered into a dark parlor on the left. Then he waited.

First he heard her. From upstairs on the second floor came the sound of quick, light steps—footsteps that sounded like a child’s. Then she entered. A plain woman with two bands of reddish hair, not particularly good-looking, wearing a white piqué dress. The white stunned him. It was exquisite. A blue worsted shawl covered her shoulders. She seemed fearful to him, breathless at first, and extended her hand—not to shake, but to offer something. “These are my introduction,” she said, handing him two daylilies. “Forgive me if I am frightened; I never see strangers & hardly know what I say.” Then Dickinson looked at him. A tall man in his mid-40s with a joyful face, she thought. Dark-haired, whiskered, graceful, he looked kind. Higginson did not reach into his pocket to fish out a topic for conversation. He did not need to.

Once they sat, Dickinson began talking and she did not stop. When she experienced eye problems several years before, she told him, “it was a comfort to think that there were so few real books that I could easily find some one to read me all of them.” She wondered how people got through their days without thinking. “How do most people live without any thoughts,” she said. “There are many people in the world (you must have noticed them in the street) How do they live. How do they get strength to put on their clothes in the morning.” She was full of aphorisms, sentences that seemed to have been crafted earlier in her mind and that she wanted to share. “Women talk: men are silent: that is why I dread women; Truth is such a rare thing it is delightful to tell it; Is it oblivion or absorption when things pass from our minds?”

At times, Dickinson seemed self-conscious and asked Higginson to jump in. But every time he tried, she was off again, and words tumbled out, almost uncontrollably. He tried to recall every phrase, every thought, even her tone, humor, and asides. “My father only reads on Sunday—he reads lonely & rigorous books,” she said. Once, she recalled, her brother, Austin, brought home a novel that they knew their father would not condone. Austin hid it under the piano cover for Dickinson to find. When she was young, she said, and read her first real book, she was in ecstasy. “This then is a book!” she had exclaimed. “And are there more of them!” She boasted about her cooking and said she made all the bread for the family. Puddings too. “People must have puddings,” she said. The way she said it—so dreamy and abstracted—sounded to Higginson as though she were talking about comets.

Dickinson said her life had not been constrained or dreary in any way. “I find ecstasy in living,” she explained. The “mere sense of living is joy enough.” When at last the opportunity arose, Higginson posed the question he most wanted to ask: Did you ever want a job, have a desire to travel or see people? The question unleashed a forceful reply. “I never thought of conceiving that I could ever have the slightest approach to such a want in all future time.” Then she loaded on more. “I feel that I have not expressed myself strongly enough.” Dickinson reserved her most striking statement for what poetry meant to her, or, rather, how it made her feel. “If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire can ever warm me I know that is poetry,” she said. “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way.” Dickinson was remarkable. Brilliant. Candid. Deliberate. Mystifying. After eight years of waiting, Higginson was finally sitting across from Emily Dickinson of Amherst, and all he wanted to do was listen.

It struck Higginson that the time he spent with Dickinson that day had been an act of self-definition for her: Her torrent of words was like a personal and literary manifesto. She reminded him of Bronson Alcott, Louisa May’s father—although Dickinson was not pompous or overbearing. Before he rose to leave, Dickinson placed a photograph in his hand. It was an image of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s grave, a memento a friend had brought back from Europe and presented to her a few days before. He accepted the gift reluctantly, knowing that it probably meant more to her than it would to him. Like with the daylilies from earlier, he knew the photograph was Dickinson’s way of saying thank you. “Gratitude is the only secret that cannot reveal itself,” she told him. Higginson said he hoped to see her again sometime, and she abruptly interrupted him. “Say in a long time,” she corrected, “that will be nearer. Some time is nothing.”

With a hundred thoughts whirling in his head, Higginson retraced his steps back to the hotel. He needed to go to bed. But before turning in, he compiled notes, trying to recall it all, and made a quick entry in his diary. Meeting Emily Dickinson quite equaled my expectation, he wrote. It had been a momentous day, one he would never forget. As he turned down the lamp, he hoped he would be able to calm his mind and get to sleep. He wanted to wake up early before catching the train to Vermont.

For Dickinson, Higginson’s visit felt unreal, as if a phantom had entered the family parlor and transformed it. “Contained in this short Life / Are magical extents,” she wrote. She felt elated, emboldened, and slightly off-kilter. Hearing herself talk so much, she said, made her feel as though the words rushing out were not sentences at all, but events. After the visit, Dickinson reached for the family Shakespeare and turned to Macbeth. “Now a wood / Comes toward Dunsinane,” she read, reliving how mystical her friend’s visit had been.

Yet as exhilarated as she felt, it was gratitude that lingered. When she thought about all Higginson had done for her—answering that first letter, writing her from the battlefront when he was wounded, continuing to write even when he felt that his life had lost its purpose, urging her to take time to perfect her art—she felt herself nearly speechless. Higginson’s generosity “disables my Lips,” she said, and magic, “as it electrifies, also makes decrepit.” It was not only that he had read her poems—although she was thankful for that. It was that he had been constant. When she sought words to thank him, she reached not for metaphors from nature or images of planets and dreams that she had been working with. She went deeper. She chose anatomy. “The Vein cannot thank the Artery,” she told him, “but her solemn indebtedness to him, even the stolidest admit.” Over the next months, the thought of seeing him again played in her mind with eerie repetition. It “opens and shuts,” she said “like the eye of the Wax Doll.” She hoped he would return to Amherst someday or in “a long time”—perhaps that would be nearer.

ostling along on the tracks to Vermont, miles from Amherst, Higginson noted down that Dickinson had dazzled him, but had also made him uncomfortable. It took every ounce of his being to meet her level of intellectual intensity. “I never was with any one who drained my nerve power so much,” he admitted. “Without touching her, she drew from me. I am glad not to live near her.”

Higginson never got around to asking Dickinson if she was interested in preparing a book of poetry. Perhaps he couldn’t find the nerve, feeling that if he pressed too hard, she would withdraw, vanishing like those sparkles of light he always associated with her. But Higginson knew there was a time to sow and a time to reap. For Emily Dickinson, the harvest was yet to come.

This piece is adapted from These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, published in February by Norton.

Martha Ackmann is a journalist and an author. Her books include The Mercury 13: The True Story of Thirteen Women and the Dream of Space Flight and These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson.